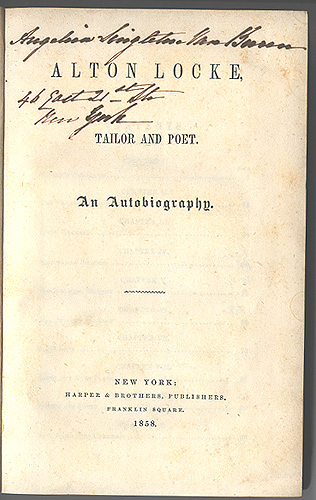

The full title of Charles Kingsley’s narrative reads, Alton Locke, Tailor and Poet, An Autobiography (1850). The story outlines the life a young man growing up during the age of Chartism.

Alton Locke is the titular protagonist of the novel. At the outset, he declares that he has “learnt–to be a poet–a poet of the people.” He grew up in London a “sickly, decrepit Cockney” and becomes indoctrinated into the a tailor’s trade. In spite of his mother’s religious fanaticism, he endeavors to self-educate himself, which inspires one of his mentors to proclaim him a “thorough young genius.” This process of self-education leads him on a journey of the self. That his growth is highly detailed, conveying the significant change he undergoes as a human being, the novel falls into the category of a bildungsroman.

Alton’s Mother is a fanatically religious woman, brought up an “Independent,” which accounts for the stern Puritan element of her disposition. After Alton’s father died, she became a Baptist. Her ancestors suffered under the Star Chamber’s misuse of power, and fought on the side of Cromwell. She is a woman who moves by “rule and method,” highly protective of Alton from the sin of the world, and she flames with anger when he argues with a pair of visiting ministers on matters of theology. Because Alton’s uncle cares for the Locke family at “five-and-twenty pounds a year,” he acts on the right to send Alton to a tailor’s workroom; the news makes his mother cry, and the next day she takes him to the shop to leave him a “lamb in the midst of wolves.” Alton’s participation in the job and its ribald nature creates distance between mother and son; she grows to become cold to him. The freedom Alton experiences after a day’s work leads him to seek out a bookstore; upon discovering his pursuit of non-biblical knowledge, she calls on the ministers to fix him. Alton’s suspects that she hired a spy to watch him, and after having been detained at work one evening, he argues with her in anger that will be a “free-thinker.” The tirade offends her to the point of demanding that he vacate the premises. After leaving, the scope of the event weighs on him and he attempts to reconcile with her, without success; she becomes the mother he “should never see again.”

Susan is Alton’s sister, a “slender, pretty, hectic” girl who grows up to become like her mother, steeped in the doctrine of religious dogma. Alton’s penchant for dissenting against ministers and their version of belief creates a rift in their relationship. By the time of their mother’s death, Susan becomes “sour, with coarse grim lips,” with an almost “dishonest look about the eyes, common to fanatics.” When Alton learns of her intention to marry Mr. Wigginton, he sinks “deeper still into sadness.”

New Zealand Missionary: Alton had learned about missionaries in Tahiti and New Zealand, and is marveled to learn that one has lately returned to London and is coming to visit the Locke family with two of the local ministers. Alton imagines the man to be a “tall, venerable-looking man,” and is startled to find that he is, in fact, a “squat, red-faced, pig-eyed, low-browed man.” Alton is appalled by his boisterous and contradicting nature, noting how the man talked of the natives “not as St. Paul might of his converts, but as a planter might of his slaves.”

Bowyer is a “little, sleek, silver-haired” old minister who always has “lollipops in his pocket for me [Alton] and Susan.”

Mr. J. Wigginton is Bowyer’s friend, another Baptist preacher who is younger, but “tall, grim, dark, bilious, with a narrow forehead.” A man who Alton hates, he preaches loudly at the chapel from the antinomian perspective.

Alton’s Father is a man Alton cannot remember. He was a “retail tradesman in the city,” though when he was young he worked in a grocer’s shop. After failing to succeed at running a business, in a neighborhood with too much competition, he died heavily in debt, leaving the family as beggars.

Alton’s Uncle is his father’s brother who, like Alton’s father, worked in the grocer’s shop, yet he steadily rose in life as his father fell. Alton’s mother tells him how they are “entirely dependent on him…for support.” Alton’s uncle is the type of person who wears a “black velvet waistcoat, [and a] thick gold chain,” and who is over-weight so that he has “acres of shirt-front.” He provides for the Locke family and one day has the young Alton report to a tailor’s shop so he can start working. He has none of Alton’s mother’s “puritanical notions,” and offers Alton support should he decide to pursue his writing.

Mr. Smith owns the shop where Alton becomes a tailor’s apprentice. He was “proud, luxurious, foppish…but honest and kindly enough.” When he dies, his son takes over the shop, announcing that for the purposes of remodeling the shop, so he can “make haste to be rich,” the workers must start doing their work at home.

Mr. Jones is the foreman of the tailor’s shop, a workroom which stifles one “with the combined odours of human breath and perspiration.”

John Crossthwaite, one of the workers in the shop, he defends Alton when Jemmy Downes grabs him by the head after rambling on about death by Tuberculosis. “Silent, moody, and preoccupied…yet king of the [work] room,” Alton is “strangely drawn to him,” though he shrinks from him upon learning he is a Chartist. Crossthwaite is “small, pale, and weakly,” but like Alton, he drinks only water; plus, he is a vegetarian. Sandy Mackaye finds his opinion “o’ ye satisfactory,” and he despises the red-coats, for they cut his father down at Sheffield because “he would not sit still and starve.” When the shop learns about having to work at home, Crossthwaite gives a speech outlining the need for equality, which inspires Alton to become a Chartist “heart and soul.” Crossthwaite comes to agitate and lecture from “London to Manchester, and Manchester to Bradford,” never without listeners, and joins Alton in reclaiming the life of Mike Kelley, his wife Katie’s brother, and Billy Porter, young men who got caught up in a sweater’s den. When Alton goes on trial for sedition, riot and arson, Crossthwaite is there to stick up for him, and his home is where Alton goes after prison. At this point they argue about the notion of initiating a revolution, and after Alton’s dream sequence, he wakes to find Crossthwaite there by his side with his wife. It is Eleanor, in Crossthwaite’s presence, who opens Alton’s eyes to what she interprets as God’s true nature, prompting Crossthwaite to remark, “what infidels we have been!” Alton and Crossthwaite, with Katie, they ultimately travel to America, where Crossthwaite writes a letter from Galveston, Texas declaring that Alton died on board ship as soon as they arrived.

Jemmy Downes is a rough-edged, alcoholic workman who gives Alton a hard time when they first meet. He gets turned away from the shop, not having paid “some tyrannical fine for being saucy.” He becomes something of a traitor to the Chartist cause, and long after Alton has grown up, Alton encounters him in his task to rescue Billy Porter and Mike Kelly. Jemmy Downes is married to an Irish woman who dies amid atrocious living conditions, along with their children. The trauma overwhelming, he dies himself a gruesome, possibly suicidal death.

Mr. Willis & Mr. Stultz: Kind master tailors “who have built workshops fit for human beings.” Their honorable mentions are based on the improvements they inspired in the morals of tailors and their artisans.

Sandy Mackaye owns the old book shop where Alton endeavors to self-educate himself. He’s an old Scotchman who has a “great fancy for political caricatures,” speaks with a thick, Scottish accent, and provides Alton with advice on various life issues.

Mr. O’Flynn is an Irish orator who becomes editor of the Weekly Warwhoop. Alton gets a job as a hack-writer working for O’Flynn, a man who comes to subsist by “prophesying smooth things to Mammon.” O’Fynn is a publishing agitator with a seedy past intermixed with strong morals, and a man who never wrote a line “on principle, till he had worked himself up into a passion.” Alton has trouble working for O’Flynn because it makes him “cynical, fierce” and “reckless,” but his problems exacerbate when he learns of Alton’s stay at Cambridge, and also when he’s asked to rewrite an article that rails against the land-owning class. After Alton’s scandal, at his trial, O’Flynn lavishes sentimental warmth on the “broth of a boy” for his courage.

Costello is the policeman who accost Alton when he stands outside his mother’s house, moments after she told him to leave.

George is Alton’s cousin, a Cambridge undergraduate who takes Alton for his first visit to a paint gallery. George is of a higher class than Alton, a young man able to have his education paid for. The two argue about the nature of education and the clergy in England. While they experience a discrepancy that sets them at odds with each other, George eventually meets with a terrible fate.

Lillian Winnstay ignites passion in Alton’s life when he sees her at the gallery, and she quickly becomes the Petrarchan object of his obsession. She is “Beautiful, beautiful, beautiful, beyond all statue, picture, or poet’s dream,” but she is romantically inaccessible because of her social status, leaving the scene of their first meeting in a carriage with “arms upon it.” Lillian continues to be the object of his desire, singing and playing piano at times, yet she dangles on the fringes of his life throughout.

Lizzy & Ellen: When Sandy Mackaye takes Alton on a tour of the London slums, Ellen is the “sick girl who tried to raise herself up and speak, but was stopped by a frightful fit of coughing and expectoration.” Lizzy is one of the girls who was “stitching busily” the skirt of a riding-habit that Ellen had to use as a blanket.

Katie: Crossthwaite’s wife.

Mike Kelly, Katie’s brother, is a “scatter-brained Irish lad.”

Young Man, Clergyman & The Labourer: After the Chartism protest fails, Sandy Mackaye suggests that Alton go to Cambridge with his poems; on his way, he meets a young man with a fishing-rod and a basket, who allows Alton to enter the woods to “see what a wood is like.” The young man is a “gentleman,” Alton’s way of distinguishing his upper class status. Alton then sees a clergyman being hard on a schoolmaster. He ask a labourer who is walking in his direction, who appears to live in a state of “perpetual fear and concealment,” about the clergyman’s situation.

Bob Porter, a.k.a. Wooden-house Bob, is a “tall, fat, jolly-looking” farmer who gives Alton a lift during his venture to Cambridge. He offers “five, or ten, or even twenty pounds” to find his son, who is lost in London.

Billy Porter, the son of Wooden-house Bob, is a red-haired, “very tall and bony” Irishman who fell victim to the sweater’s trade.

Lord Lynedale: In a burst of cheering for his cousin George, Alton gets slammed into the water by Lynedale. He hires Alton to proofread some of his work, which leads to Alton’s possible opportunity of becoming a student.

George’s Brother, a man who “has no brains,” joined a cavalry regiment instead of pursuing education like his brother.

Dean Winnstay: Alton spoke with the dean unwittingly at the gallery. On Lord Lynedale’s referral, the dean reads Alton’s poetry. He’s not a fan of Shelley, and he offers Alton a possible sizarship, contingent upon the prospect of studying mathematics or nature, as long as it’s not poetry.

Eleanor Staunton loves Lord Lynedale. She has “glorious black-brown hair,” and one day, while discussing philosophy with Alton, she turns to the approaching Lynedale with a “look of tender, satisfied devotion.” Alton perceives her endeavors to keep Lillian away from him, but eventually finds out why.

The old Jew & The Jew-boy: At the sweater’s den where Alton finds the missing Billy Porter and Mike Kelly, the old Jew is a “most un-Caucasian” person who answers the door and who rants about how the workers owe him money; the Jew-boy is apprehended in mid-flight attempting to lift a “heavy pocket-book” from Wooden-house Bob.

Mr. Windrush is an American, once a Calvinist preacher, who speaks with a resemblance to Ralph Waldo Emerson.